Stripping Off Later Additions

The statue is seen from the back after removal of all later additions, and without the proper right foot, which was taken off to be conserved separately.

A photocopy of a lost photograph shows the statue of Saint Paul the Hermit upright, before it lost the rock with the billowing end of the straw mat.

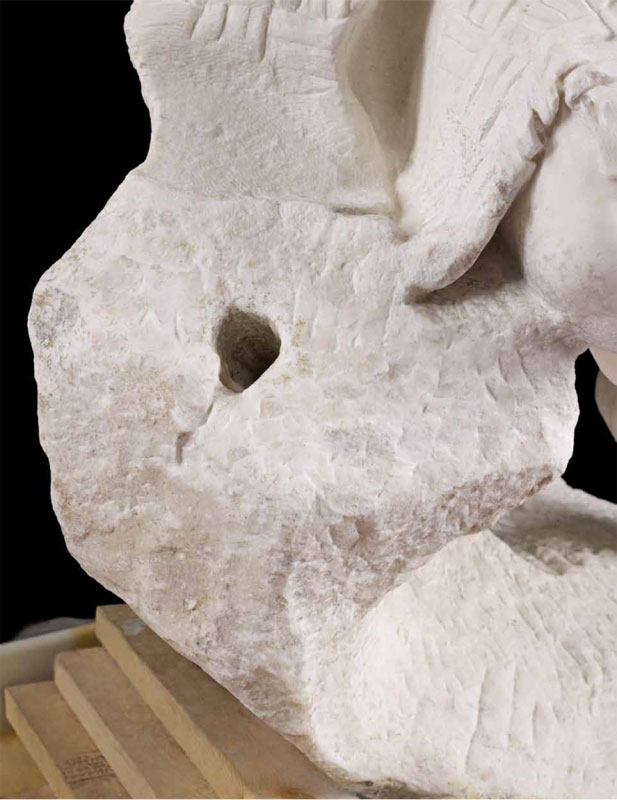

As the presence of a large drilling hole for a rod suggests, the missing end of the statue may well have been carved out of a separate piece of marble, or it may have been broken and reconnected with the main part of the sculpture at an earlier point in its history.

A photocopy of an old photograph, which has survived in the MIA’s object file, shows the statue of Saint Paul the Hermit upright, with his proper left knee propped against a marble rock, on top of which the woven straw mat (made of palm leaves), which the saint wears around his hips, billows in the wind. The lost photograph must have been taken in the early 1960s or before, when the statue was still intact. The parts now missing most probably were severely damaged and lost during transportation, perhaps within Rome or on the way from Rome to London.

Having lost its left end, the statue was mounted with the figure tipped forward by about 45 degrees. This may have been an attempt to better stabilize the sculpture, but it obscured its meaning. Instead of praying upwards to heaven, Saint Paul seemed ready to jump off a rock for a swim.

Repositioning the Statue

After taking off the later additions, conservators, curators, and preparators chose a position that approximates the statue’s original upright stance. They had to take into account the different center of weight compared to its earlier state, which included the rock with the billowing drapery.

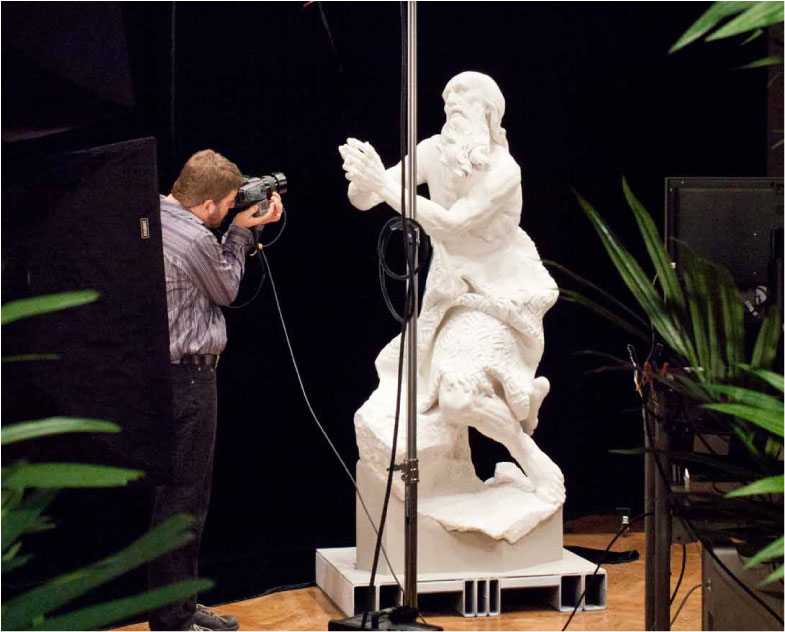

Charles Walbridge, MIA Visual Resources photographer, takes final photography for the museum’s Web site and future publications.

Hanging in a gantry, the figure’s new position is locked in with wooden planks, which were later nailed together to hold the statue in place. From left, Eike D. Schmidt, exhibition curator, Nicole Grabow, associate objects conservator, Jack Buss, senior preparator, and Bill Skodje, senior preparator.

Saint Paul is rolled into a different working space in a specially constructed wooden cage. Wooden boards on the cart’s floor keep him in his newly regained upright position.

A wooden model for the base was built and tested on the statue. A stainless steel base was welded according to the wooden model.

Body Extensions

For the most part, the figure of Saint Paul the Hermit is carved out of a single block of marble, following the ancient ideal of ex una lapide (out of one stone). While it was more challenging for the sculptor to carve a statue of a single block of stone—since this approach would not allow for the slightest accident or mistake—and more costly to cut a large block of good quality in the quarry and to transport it to the sculptor’s studio, this practice ensured greater stability and durability compared to a statue pieced together of many different parts. Moreover, the result is aesthetically more pleasing, since the fissures between the parts would become visible after any gesso that might have been used to cover up the joints would crumble away.

The saint’s right foot was carved separately. It was shattered and repaired at some point during the statue’s long journey. During the conservation process, the individual parts were taken apart and cleaned. Rusty rods and staples were extracted and replaced with a new rod made of stainless steel.

An X-ray image taken before conservation shows multiple breaks as well as rods and staples holding together the foot and joining it to the leg.

However, two parts that probably extended beyond the marble block’s perimeter—the proper right elbow, and the proper right foot—were carved separately and attached with metal rods. An alternative interpretation is that these parts were damaged at some point in the statue’s history and reattached or even replaced.

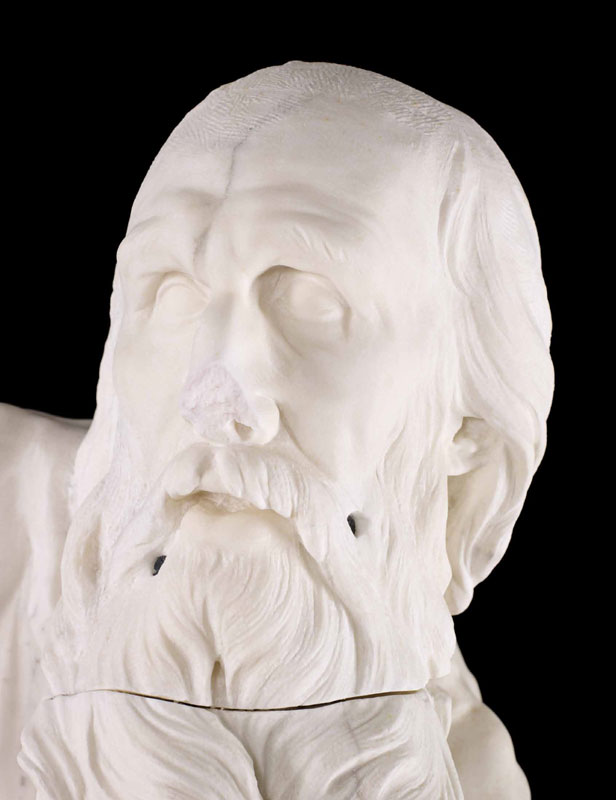

Similarly, the saint’s long beard was carved separately. This might have been necessitated by a carving error by which the original beard broke, or by the emergence of an unsightly or unstable dark vein within the marble in that area. It is also possible that the block was roughed out in the quarry without taking the beard into account, either by mistake or in order to make the most of the material and to reduce its weight as much as possible.

Since the carving of the beard follows the same style above and below the join, it is not probable that the tip of the beard is a later replacement.

The saint’s right foot was carved separately. It was shattered and repaired at some point during the statue’s long journey. During the conservation process, the individual parts were taken apart and cleaned. Rusty rods and staples were extracted and replaced with a new rod made of stainless steel.

An X-ray image taken before conservation shows multiple breaks as well as rods and staples holding together the foot and joining it to the leg.

A new stainless-steel rod was inserted into the existing hole to reconnect the foot to the leg.

The beard was attached in a more complex way, using rods that were secured through two piercing-like holes near Saint Paul’s mouth. The tip of the nose, which had been damaged and hastily repaired at some point in the statue’s history, was cleaned out and remodeled, strictly following the outlines of the marble nose.

Traces of Tools

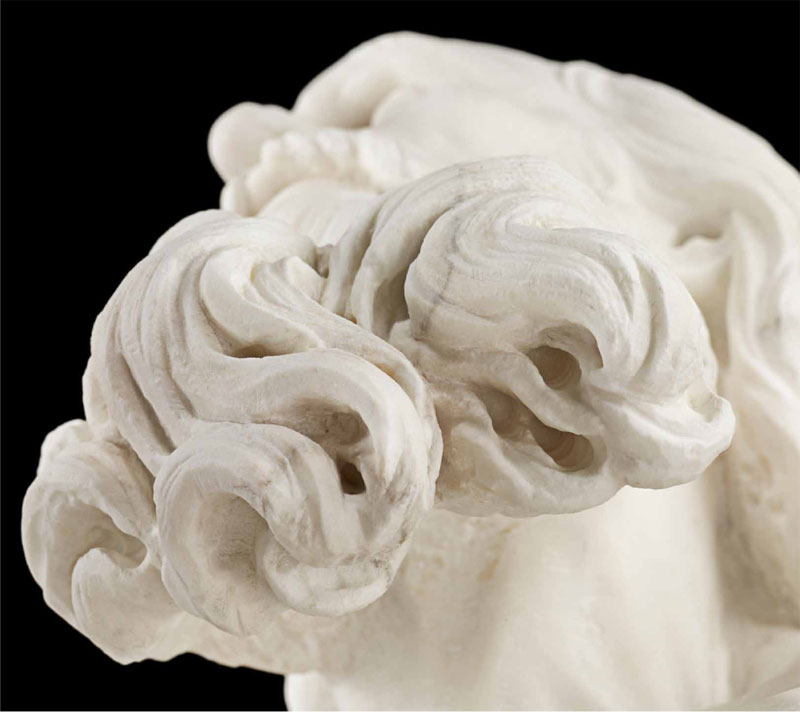

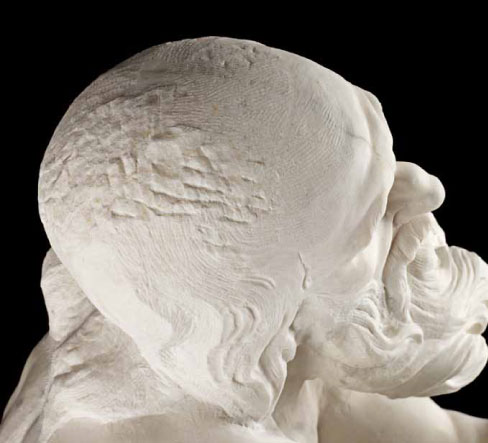

A cord drill was used to riddle the beard with holes, in order to render it as lively. This technique, which was particularly fashionable in Rome during the 17th century, shows how carefully Bergondi studied High Baroque examples even from a technical standpoint.

Since the statue of Saint Paul the Hermit was installed at a high vantage point beyond the high altar of the church of San Paolo Primo Eremita, areas that would not be seen were left unfinished. The present installation on the ground provides the unique opportunity to see remnants of earlier strata and phases of the statue’s finishing process. Traces of all three types of finishing tools can be found on the statue’s surface: the point chisel (leaving rough, linear traces), the tooth chisel (with smaller, parallel traces) and the flat chisel (leaving a smooth surface). Traces of coarse-tooth chisels and fine-tooth chisels can be seen in numerous places on the statue’s back.

Closeups

The statue of Saint Paul the Hermit before restoration, as it was mounted in or shortly before 1965.

The statue of Saint Paul the Hermit before restoration, as it was mounted in or shortly before 1965.

The marble surface is cleaned with a soft brush.

The next stage in the cleaning process involves damp cotton swabs (shown here) and poultices.

New fill material in the gap between two parts of the beard is carved with a scalpel.

Associate objects conservator Nicole Grabow applies steam with gentle pressure to the marble during the final cleaning phase.